The body landed in the courtyard, not far from the building’s bins. Shortly before 5am on 4 April 2017, a 65-year-old woman was hurled from the third-floor balcony of a social housing project in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, a rapidly gentrifying area on the eastern side of the French capital. An hour earlier, that same woman – a retired doctor and kindergarten teacher – had been asleep in the small apartment where she had lived for the past 30 years. When she woke up, she saw the face of her 27-year-old neighbour in the darkness. The man, who still lived with his family on the building’s second floor, had first stormed into another apartment, whose tenants had locked themselves in a bedroom and called the police. By the time he climbed up the fire escape into his victim’s apartment, three officers were present in the building.

The autopsy would later reveal that the woman’s skull had been crushed, most likely with the telephone on her bedside table. Before and after his victim lost consciousness, the assailant beat her until the nightgown she was wearing – white, with a blue floral pattern – was soaked with her blood. He then dragged her body to the balcony of the apartment, and threw her over the railing – exactly the same way, he told prosecutors, as John Travolta does in The Punisher, the film he had been watching before the attack. “I killed the sheitan!” he yelled from the balcony, according to testimonies given by neighbours. “Sheitan” is an Arabic word for “devil”. Neighbours heard him repeatedly chant “Allahu Akbar”.

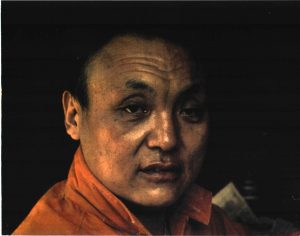

The victim was Lucie Attal, an Orthodox Jewish woman who sometimes used the name Lucie Attal-Halimi. The perpetrator, who confessed to the crime, was Kobili Traoré, a Franco-Malian Muslim. He later told authorities he knew that his victim was Jewish. According to her family, Attal had long felt afraid of Traoré. Her brother, William Attal, told me that Traoré had verbally abused her in the building’s elevator, and she had said she would only feel safe if he were in prison. In fact, Kobili Traoré may never go to prison for the killing: he has been in psychiatric detention since the night of the crime, and a French judge could rule that he is mentally unfit to stand trial.

In the immediate aftermath of Attal’s death, there was virtually no public discu

ssion of her killing. With the upcoming presidential election dominating headlines, the defenestration of a Jewish woman in the 11th arrondissement of Paris was treated by the mainstream French press as a fait divers, the term used to describe a minor news story, which led to considerable outcry in the Jewish community. But after the victory of Emmanuel Macron, the case returned to the forefront, becoming a new frontline in France’s culture wars, among the most explosive in Europe.

The French Republic is founded on a strict universalism, which seeks to transcend – or, depending on your viewpoint, efface – particularity in the name of equality among citizens. In a nation that tends to discourage identity politics as “communautaire” and therefore hostile to national cohesion, the state not only frowns on hyphenated identities, but does not even officially recognise race either as a formal category or a lived experience. Since 1978, it has been illegal in France to collect census data on ethnic or religious difference, on the grounds that these categories could be manipulated for racist political ends.

But eliminating race did not eliminate racism or racist violence. In the case of Lucie Attal, the inescapable fact of the matter is that a Muslim killed a Jew in a society where those distinctions are supposed to be irrelevant. More than a year after the fact, exactly how to label Attal’s death remains a matter of bitter, and perhaps unresolvable, debate. To examine the case is to examine the fractures of the French Republic, the contradictions in the stories a nation tells itself.

Traoré has vehemently denied that antisemitism played a role in his crime, claiming instead that he acted in the throes of a psychotic episode triggered by cannabis. But for William Attal, the only way to understand his sister’s death is as an act of antisemitic violence. “He knew very clearly that Judaism was the motor of her life, that she had all the external signs of Jewishness,” Attal said. When we met in a cafe in the Paris suburb of Nogent-sur-Marne, he wore an anonymous red baseball cap instead of anything that might identify him as Jewish. “We have the obligation to cover the head, but we do not have the obligation to wear a kippa,” he said. “Understand?”

In February 2018, after considerable public outcry from Jewish organisations, who accused the criminal justice system of a cover-up, a French judge added the element of antisemitism to the charges against Traoré. But the case is far from closed. In July 2018, a second court-ordered psychiatric examination declared that the perpetrator was not of sound mind and was unfit to stand trial; a third examination is forthcoming. If he cannot be held accountable for his actions, Traoré cannot, legally speaking, be said to have had a motive. There is the possibility that Attal will have officially died in a random act of violence, as if she had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

During the months of confusion, indecision and silence that followed the killing, people from every side of France’s political debate seized upon the case as evidence of whatever position they already held. In time, the story of Lucie Attal would become the inspiration for any number of politicised narratives, hardly any of which took into account the woman who had died, or even her actual name.

On 10 April – one week after the killing and three weeks before the presidential election’s first round – Marine Le Pen sat down for an interview with the newspaper Le Figaro. Two days earlier, Le Pen had shocked much of the country by claiming that the Vichy government’s participation in the Holocaust “was not France” and insisting that France was “not responsible” for the so-called Vel d’Hiv roundup of Parisian Jews in 1942. It was time, she said, for the French to be “proud to be French again”.

The Vel d’Hiv roundup ranks among the darkest days in modern French history, and is known even to schoolchildren as a synonym for national shame. On 16 July 1942, approximately 13,000 Jews were arrested and detained in the now-demolished Vélodrome d’Hiver racing arena in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. From there, they were deported to Nazi concentration camps. Few of the deportees ever returned. What lingers in public consciousness is this: it was French police officers who carried out this assault on their fellow citizens, not their Nazi occupiers.

Pressing Le Pen on her Vel d’Hiv comments, the journalist from Le Figaro asked how she would respond to the con

གདན་ས་ཁམས་པ་སྒར་འབྲུག་མཐོ་སློབ་དྷརྨ་ཀཱ་ར།

གདན་ས་ཁམས་པ་སྒར་འབྲུག་མཐོ་སློབ་དྷརྨ་ཀཱ་ར།